Iraq holds many historical treasures that are yet to be discovered. Going back to the first civilisation, Mesopotamia is slowly appearing on the surface from under the sand and dust accumulated over thousands of years. The discoveries of Dr Sébastien Rey, Archaeologist and Curator of Mesopotamia at the British Museum, revealed the spirituality, values, and lifestyle of the ancient civilisation of Mesopotamia, through an excavation he leads at Girsu for 8 years in a collaboration with the British Museum.

Tell us about the Girsu excavation project, its location, and your involvement in it.

Girsu is a heritage site in South Iraq. Online or in books on the history of Mesopotamia, you may know the site as Tello. That’s its modern name. The ancient name of this Sumerian site is Girsu. It’s one of the very first cities of Mesopotamia. It’s a very well-known site in the sphere of academia. A 150 years ago, it was one of the most important sites in the world, and a lot of people knew about it because it made the front pages of many newspapers in Europe, Iraq, and Istanbul. The reason is that in 1877, this site of Tello was revealed to the world and showed the existence of the Sumerian civilisation. Our knowledge, if you think of the 19th century first pioneering exploration of Iraq, especially in the north around Mosul where there are great discoveries of the ancient Assyrian capitals of Nineveh, of Nimrud, and the knowledge of Babylon, the reality is that at that time, the existence of the Sumerians, which is a much more ancient civilisation, was unknown to the general public and to academia.

With the discovery of this site in 1877, the first excavations at the site led to the discovery of the Sumerians. Girsu was a very important city, one of the first cities. When we think of the Sumerian culture, the Sumerian heartland in the south of Iraq, we think of Ur, of Uruk, of Eridu, and Girsu was one of those big, important religious centres. It was a sacred city dedicated to one of the gods of the Sumerian Pantheon, the Hero God. His name was Ningirsu, so the Lord of the City of Girsu. He was extremely important for the Mesopotamians for thousands of years. This is because the God of the City of Girsu, was the hero, the warrior God of the Sumerian gods. He was responsible to protect the heartland of Sumer of southern Iraq, against evil forces that would descend from the edge of the world, from the mountains into the plain of southern Iraq to cause chaos and destruction.

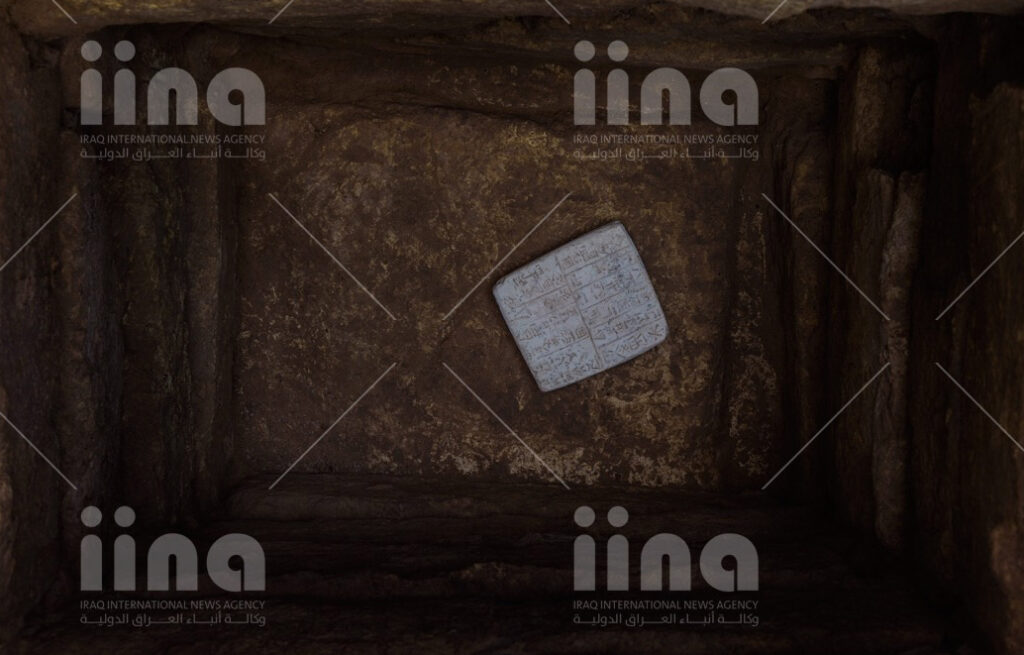

His role was really to shield and to defend the Sumerian world and the Sumerian people. That’s why he was very important and worshipped, not just in the city of Girsu, but all across the south of Iraq. We have a lot of information from the cuneiform tablets, the clay tablets, that record a lot of information from that time. For a thousand of years, starting at the very beginning of the third millennium, we know that pilgrims from all across Mesopotamia would go and visit the Holy City of Girsu several times a year in very large processions. So, this was a major centre of cult in the third millennium BC.

I joined the museum back in 2016. I came from Europe to work with the British Museum on one particular project, which was called at the time the Iraq Training Scheme, which was funded by the UK government at the time. The reason I was interested to be part of this project is that the government of the United Kingdom, back in 2016, decided to do something after the disastrous destructions of cultural heritage in Iraq. There was a big fund, which was called the Culture Protection Fund, which was created. The government asked the British Museum to start a training programme for our colleagues in Iraq in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture in Iraq, to come up with a plan to do something to provide some help and assistance to our colleagues on the ground facing the destruction of their cultural heritage.

That’s how I got interested in this project. There was a double objective of, firstly, providing some help by bringing equipment. That’s what our colleagues in Baghdad requested at the time. They needed the software, the technical skills to start recording all the damage and destruction at sites that had just been liberated by the Iraqi army. So, that was one of the first goals, to train in the field, not simply in a classroom setting, to go really in Iraq at a site and to give them some training using the equipment that they would then be using in the north of Iraq. Now, the reason that we selected a site in the south of Iraq is that it was a safe area for us to deliver our training sessions. Training sessions were delivered by a group of international experts coming from all across the world and also Iraqi colleagues delivering training in the south of Iraq.

How was the Girsu site found?

It was found in 1877 by a French diplomat who was at the time posted in Basra. So, the late 1870s was under the Ottoman Empire. There was three vilayets that are Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra. So, Ernest de Sarzec, the French Council travelled north and visited the site of Tello. At the time, they didn’t know it was ancient Girsu and he started excavating the site in 1877. Then, he worked on behalf of the Louvre Museum which excavated the site from the time of Sarzec all the way down to the 1930s. So, there were extensive excavations and very destructive excavations that compelled us to go back to that site, because those old excavations created a huge issue for the modern site itself in terms of conservation and preservation. You have to remember that at the time, the pioneering excavations, all foreign excavations, had hundreds of workmen. They were excavated at a great speed. They didn’t have the skills and the equipment that we have today.

Talking about conservation, what are you doing now to protect the site? And what are the ways you came up with in order to have a good conservation, even to pass it on to younger archaeologists?

The first question I had was, how should I, as an archaeologist, engage with heritage sites today? With all of those issues that I mentioned. Well, key to addressing this question is what I believe the only way is that you have to have a holistic approach to heritage sites, especially archaeological sites. When I say holistic approach, I mean you need to be able to combine a number of things. Research by itself isn’t interesting, and a lot of colleagues working in universities are interested in research. But what do you do with the site? How do you engage with the site? When I say the site, I’m talking about not just the archaeological site. I’m talking about people living around the site, the villages, the people that are going through the site. It’s much wider. Like I said, considering the site as a real landscape with people, a living landscape, not just an ancient ruin. It’s also where people live. That’s really important. How did I start the project? Well, I contacted some heritage specialists, so people that are not archaeologists, not academics, but who are working on these important questions.

There are a few people that are doing this today. I worked with the core team. You can see the names of the team that work with me on the British Museum website. But the heritage manager, her name is Ebru Torun, and my co-director is Iraqi, her name is Fatma Hussain. Both of them, have structured and defined a heritage plan for the site. The first thing is doing consultations with the people, the stakeholders, identifying who are the stakeholders. Tello is in a very tribal area of Iraq. We had to get in touch with them. We have meetings on a regular basis because they are a key stakeholder. The local population, the villages around the site, they are also very important stakeholders. And all the way up to the Iraqi government, the Ministry of Culture, because we have a permit from the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, also a key stakeholder. What we did before coming up with the miracle plan, we did a lot of consultation, trying to understand what people wanted and needed for the site.

That also includes the tourism industry. We had consultation with them, with different tour operators, with the tourism, with the mayors of the villages and the distant towns of Nasiriyah because it’s a federal state. Once we had all those discussions and consultations with all of these different stakeholders, we developed what we call the heritage plan, which is a sustainable plan. The urgent thing was the conservation element. There were Sumerian buildings, some incredible big monuments that were collapsing when we arrived. We had to set up an emergency conservation strategy. We’ve been doing this over the past seven years. Targeting really the areas of the site, some of the buildings that were excavated more than 80-100 years ago that had been left completely without any conservation strategies over the years. We’re targeting these as emergency projects. There are two big buildings at the site.

One is the Bridge, one of the oldest, if not the oldest, known bridge in the world. That’s a monumental building. We are targeting, we are conserving over the six past years, and we have to continue. We haven’t finished the conservation of this bridge. We have started the conservation of a temple, a really important temple dedicated to the garden in Girsu. These are big conservation projects. But in addition to that, what is crucial and part of the DNA of the project is that we are sharing knowledge. We are also having students from universities all across the country, not just in the south of Iraq. So, we have students from Mosul, Kirkuk, and Baghdad coming to the site. They are having intensive training with those conservators and heritage specialists to understand the principle of conservation and to do some of the conservation work themselves. We work with students and we also work with employees of the state board to enhance their own knowledge and having those discussions on the future of sites like Tello, Ancient Girsu.

As the project director, what artefacts and objects have you found? And what is the feeling of finding these artefacts that are from thousands of years ago?

The feeling is incredible. It’s first a real honour for myself and the team. It’s a great experience, a human experience to work at this site. The research element is really important. It wouldn’t work, again, without this holistic approach. The key thing is trying to combine conservation training and research, because all of this works together. Now, when it comes to research what we decided to do from the very start of the project was not to open new areas of excavations, because that site has been extensively excavated. What we decided to implement at the site is what we call rescue excavations. One way of doing this is basically re-excavating the old French excavations from the Louvre Museum.

Over seven years, we extended our excavations and found a very well preserved remain of this ancient temple. Also, a lot of objects, religious objects that were dedicated to the God, Kings and Queens, but also the regular citizens of Girsu and of Mesopotamia at large. Every time you find some of these objects which had been deposited more than four thousand years ago, you can see the gesture of someone worshipping the ancient God and bringing an offering to the temple, and you’re re-excavating this. The connection with the past is incredible. That’s always something special when you do that, when you just walk in the footsteps of those Sumerian people from thousands of years ago.

- Published: 23rd July, 2024

- Location: Dhi Qar Governorate, Girsu city

- Country: Iraq

- Editor: Elika Bozorgi

- Category: Heritage