Art has long been a powerful means of navigating identity, history, and personal experience. For Emii Alrai, a British-Iraqi artist, sculpture and installation serve as a way to interrogate heritage, materiality, and the structures that shape our understanding of the past.

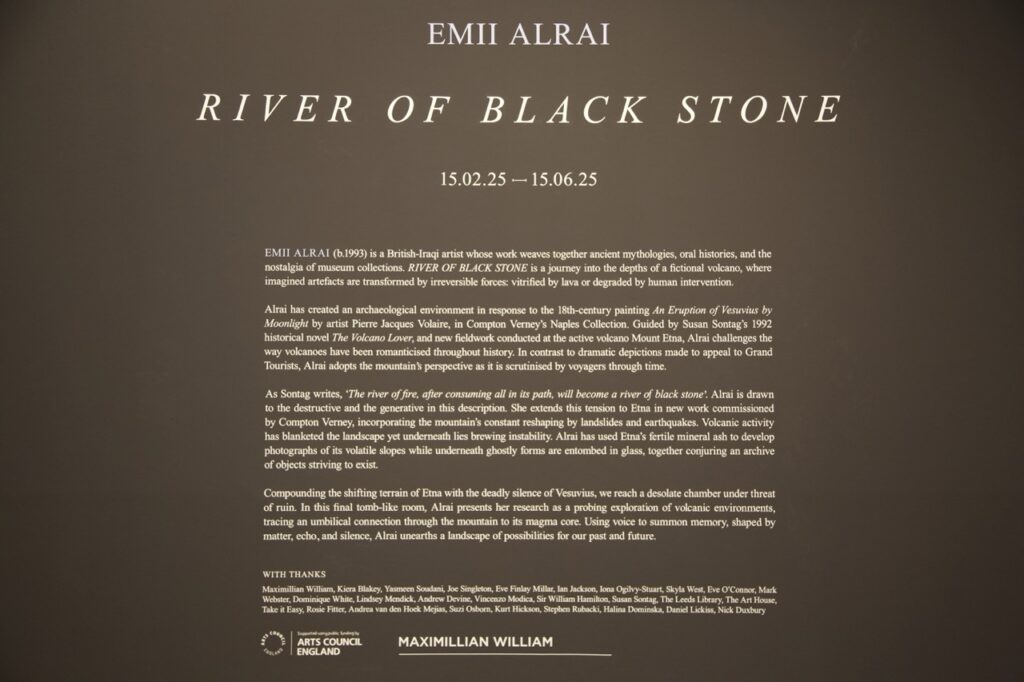

At Compton Verney in Warwickshire, Emii Alrai’s latest exhibition, River of Black Stone, which opened on February 13th, unfolds like an archaeological site in motion. The exhibition is not explicitly about Iraq, yet its influence is ever-present in Alrai’s practice. In this interview, Alrai discusses the origins of her artistic journey and how her varied experiences have influenced her practice.

You’ve worked as a museum registrar, writer, and now as an artist focusing on sculpture and installation. What first drew you to art, and how has your background shaped your creative journey?

“I have always been interested in art since a really young age. It’s always been very present in my life, from constructing worlds out of cardboard boxes at home to drawing. I always found it a space where I could just imagine. I grew up in a small place in Scotland, where it seemed like there wasn’t a lot of imagination. Art gave me a freedom that perhaps I never really felt in the landscape in which I grew up.”

Her work in the museum sector further shaped her creative approach. As a registrar—often described by her as a “travel agent for objects”—she handled artefacts, archives, and collections, gaining an intimate understanding of how history is preserved and presented. “I started to think about the romanticism of a very specific past that doesn’t belong to the system in which it’s now contained; the Western ‘museological’ structure.

This contrast between careful museum work and the unrestrained energy of the studio has deeply informed her practice. She mentions the difference between doing very careful museum work, which differs from the studio. At the studio, “things were breaking all the time; there was this really nice tension between the polish of the museum and the actual chaos of living.”

How has growing up in the diaspora shaped your connection to Iraq’s history and your artistic language?

“Where I grew up, it was almost like living in two places. At home, we had such a close-knit family—my mum, my dad, my aunties, my uncles—there was this vibrancy, warmth, dancing in the kitchen, cooking, everyone coming together. It was so different from this small town in Scotland. That contrast has been really influential, both in who I am and in inheriting language, memories, and experiences of Baghdad and Iraq through my family.”

Despite never having been to Iraq, she feels a deep connection to its heritage. “It’s always quite interesting to feel so connected to a culture I’ve only had a small snapshot of. But at the same time, it’s rich and deep in my own body and understanding through family. I try not to romanticise it, and hopefully, I get to go there one day.”

Storytelling has played a crucial role in shaping her artistic language. “There’s a richness in oral histories that have been passed down. That has really seeped into how I search for stories, narratives, and poetry in my work; how time accumulates and covers things until they become something else.” Her family’s history also influences her practice. “Keeping culture alive at home has always been important, and despite so much adversity, there was still so much laughter. That’s something I want in my practice too; a playfulness, a lightness, even when dealing with heavy topics.”

One of her earliest artistic fascinations was with the British Museum. For her, ancient history became a gateway to understanding her heritage. “As many in the diaspora experience, it’s a culture of building your own culture from the strands that remain after a severance. Beginning with ancient history felt like an easier way to connect to something that has always been there.”

River of Black Stone draws from the imagery of volcanic eruptions and the romanticism of past voyages. Iraq, too, has a layered history of destruction and renewal. Do you see parallels between the geological references in this work and Iraq’s shifting cultural landscape?

“River of Black Stone developed over months as I explored the language of eruption and volcanoes. It began with the Valère collection of volcanic paintings at Compton Verney, where I became interested in the romanticism and poetry of explosion; how we’re obsessed with brewing instability in volcanic landscapes and our desire to grasp and contain the unattainable.”

Her research led her to Naples and Pompeii, following the accounts of 19th-century voyagers who helped shape the Western obsession with collecting and preserving landscapes. “Naples is a place of such sadness and pain, yet the way it has been written about is so poetic. I started reading books from the 1800s, tracing the steps of these expeditions that, in many ways, sparked the collecting craze. That led me to Mount Etna, one of Europe’s most active volcanoes, which, very madly, erupted on the eve of the show’s opening. There’s all this poetry somehow.”

Being at Etna reshaped her perspective. “Seeing it first hand, you realise how long it takes for something to grow again, for a seed to germinate and reclaim the land. The process of shifting and rebuilding is slow, but constant. It made me think about identity; how we, too, go through cycles of destruction and renewal. Maybe that relates to Iraq, maybe to other places in the world, but there’s something really beautiful about resilience. That’s what volcanoes started to symbolise for me.”

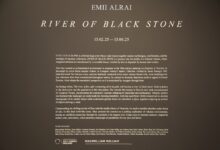

Your installations blur the line between archaeology and fiction, using materials like clay and steel to create objects that feel both ancient and speculative. Do certain materials hold personal or cultural significance for you, particularly in relation to Iraq’s artistic and architectural heritage?

“I use a lot of theatre-building techniques, often working with polystyrene to create large-scale artefacts, architectural facades, and sculptures, which are then coated with plaster. Plaster, or gips, feels like a material I’m really connected to because my dad taught me how to work with it. He used to do a lot of plaster carving on mosque facades in Baghdad, and I remember sitting with him, learning in this very traditional way that he had learned from his own father.”

Beyond plaster, she often uses materials that mimic others. “In this exhibition, I’ve made mosaics from salt dough—just flour, water, and salt—materials that are so accessible, yet can be transformed into something that looks ancient. They become almost visible, yet not, suspended in time.”

Your work questions how objects are displayed and interpreted, especially in museums. In River of Black Stone, do you see your pieces as a way to reshape how we think about history?

Her work challenges traditional ideas of value and significance. “What is it about an object that makes it important? Is it its material; copper, glass, because we’ve been told it’s valuable? Or is it the history attached to it? A spoon made of aluminium, passed down for generations, can hold more meaning than something crafted from expensive materials.” Through her pieces, she plays with these ideas, repositioning domestic objects like vases and glassworks, allowing them to be seen in new ways.

Materiality also plays a central role in her process. Many of her works are re-appropriated from previous exhibitions, carrying the marks of time and handling. “These objects start as naked forms, but over time, they accumulate histories; the hands that put them up, took them down, the scars and marks left behind. Eventually, they become valuable in their own right.” Rather than preserving objects in a fixed state, she embraces change. “I’m interested in letting things live, decay, and shift rather than being contained and held still.”

As an Iraqi artist working internationally, what do you hope audiences—both Western and Iraqi—take away from your work?

“Like any artist, I hope people enjoy the exhibitions. But more than that, I want the work to evoke something personal; whether it’s a form that stirs a memory, a scent that unlocks something buried, or a sensorial experience that activates a connection to history.”

She hopes her work challenges the way history is often presented as fixed and factual, particularly in museums, and instead invites audiences to lean into imagination. “So much is taken away from us when history is presented as fact, but imagination allows us to reclaim and reshape it. I want the work to open portals; spaces where people can build their own landscapes of history and belonging.”

For those encountering River of Black Stone at Compton Verney, the experience is immersive and contemplative. The exhibition does not offer a linear story but rather a series of encounters. Alrai invites us to reconsider how we engage with both what we remember and the objects that are left behind.

Through her sculptural works, which blur the line between archaeology and fiction, she creates spaces where imagination and memory are as significant as fact. Her installations, deeply rooted in personal and cultural histories, offer a powerful meditation on resilience, transformation, and the layered complexities of heritage. In doing so, her work not only speaks to the universal human experience but also draws from the rich, fractured history of Iraq, encouraging us to reflect on how we reclaim and reshape our own narratives.

- Published: 3rd March, 2025

- Location: Compton Verney

- Country: United Kingdom

- Editor: Justyna Wojtowicz

- Photographer: Justyna Wojtowicz

- Category: Arts, Culture and Events