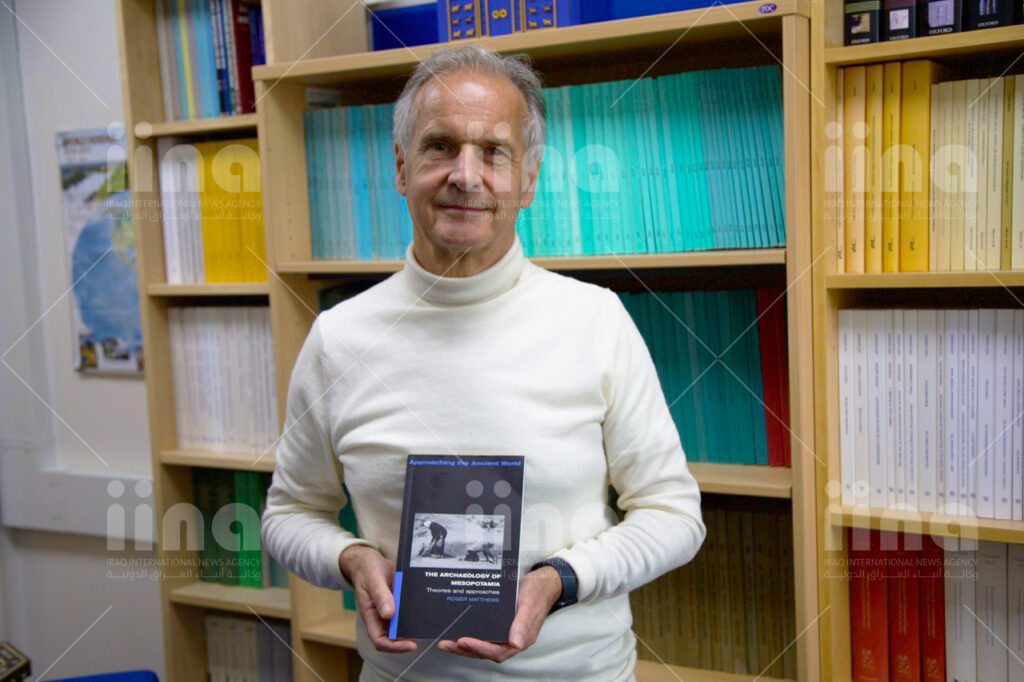

In an exclusive interview, Professor Roger Matthews, of the Archaeology Department at the University of Reading, speaks about his research and archaeological findings surrounding the prehistory and early history of the Mesopotamian region.

Given your extensive research on Mesopotamia, could you explain why this region is considered the ‘cradle of civilisation’ and what its prehistoric and early historic periods reveal about the cultural heritage of Iraq?

Well, Mesopotamia is such a critical place for studying so many episodes of the human past and of course we equate Mesopotamia which, as you know, means the land between the rivers, i.e., Tigris and Euphrates… more or less with the modern country of Iraq. In Iraq, there are so many important developments through the past and as an archaeologist, that’s what I’m very much interested in. So, in one of those developments… which I research along with colleagues here at Reading and in Iraq and many other places, we’re investigating the transition from mobile hunting and gathering of food stuffs to more settled farming, animal herding and domestication of crops like wheat, barley, peas and lentils. All of that takes place very early on in Mesopotamia, in particular Northern Mesopotamia, and especially the region in the Zagros mountains, which is the sort of border range of mountains between Iraq and Iran to the east. In that region, roughly 10,000 years ago is when there was this great transition, whereby people domesticated animals like goat and sheep, and the crops and plants that I mentioned. These then become the basic food stuffs for so much of the world today. Many of the animals that we see in Britain today, for example sheep and goat and pigs, they actually don’t originate from here. Genetically, we can track them all the way back to the Middle East, as I say roughly 10,000 years ago, when these creatures were first domesticated. So, that’s one episode that’s really globally significant as to why Mesopotamia is a key region because it is one of the first regions in the world where that happens.

Another one is in early urbanisation, whereby the world’s first cities are also developed by people in Mesopotamia, but this time especially in south Mesopotamia, so south Iraq today or Sumer, as it was anciently known. These cities date back to about 5,000 years ago, so roughly 3,000 before the common era. It’s when people started to live in very large urban agglomerations along the rivers in south Iraq, especially the Euphrates River but also the Tigris. These cities were quite complex and we know that they developed writing. The earliest writing is developed by people in Mesopotamia just over 5,000 years ago, so it’s very early and that’s the so-called ‘cuneiform’ tradition. Cuneiform means wedge-shaped, which is writing on clay tablets with a stylus and Sumerian is the oldest language that we can understand and that goes back 5,000 years. Then the whole range of other languages are written using that script, the cuneiform script on clay tablets. So, these are incredibly important developments that have an impact globally throughout time. The first farmers, the first urban dwellers, the first literate people… that all happens in Mesopotamia.

Your investigation into early writing and sealing in Mesopotamia from 3200-2400 BC has shed light on many aspects of ancient life. What are some of the most surprising or impactful discoveries you’ve made in this area? How do these findings contribute to our understanding and preservation of Iraq’s cultural heritage and human civilisation in general?

Yes, that’s right. The early writing is very much a part of a bureaucratic system that also involves the use of seals, and again Mesopotamia is the first place really in the world where people start using seals. Initially, stamp seals which are simply stamped onto the clay and then cylinder seals which have designs very carefully engraved into the stone of the cylinder, and that would then be rolled over the clay. You could just roll endless designs or iconographic scenes on clay. That is a tradition that lasts for thousands of years in Mesopotamia and it’s part of this system of bureaucracy. I mean we all live with bureaucracy today, you know, universities have a lot of bureaucracy, everyone has to do tax returns or whatever, as part of a bureaucratic system. Again, this was another invention of the Mesopotamians, so that has an impact in the way that we live today. We can trace that all the way back to people using seals and writing as a bureaucratic system from 5,000 years ago. In terms of the impact on the world today, it’s really massive and I don’t think there’s another country you could point to and say that it had such a fundamental impact on the way we live today. You know, the sort of structures and practices we have today in our lives. They can all be traced all the way back to Mesopotamia.

What are some of the main challenges you face when conducting archaeological research and preserving cultural heritage in Iraq, especially in regions that have experienced conflict or instability, and how do you address these challenges?

In terms of actually conducting research, all the research I do is with my colleagues here and in particular with my wife and co-director of the projects, Dr Wendy Matthews. We work very much in collaboration with Iraqi colleagues, so firstly with the state directorates of antiquities and heritage, and secondly with universities and colleagues in academic institutions in Iraq. It’s very much a collaborative and joint work. We work together, we publish together, we do research together, etc. The region that we’ve been working in for the past twelve to thirteen years is the Sulaymaniyah province of Iraqi Kurdistan, which is a very stable place, very quiet and calm so, like many other foreign academics, we are able to work with Iraqi colleagues on joint projects, excavations, surveys, without problem. We don’t really have those problems of instability or dangerous circumstances. It’s a safe environment, a very welcoming and encouraging environment to work in. Steadily, Iraq is getting more and more stable year by year.

How have modern technologies transformed the field of and the preservation of cultural heritage, especially in your studies of Mesopotamian sites? Can you provide examples of how these technologies have enhanced heritage conservation?

Archaeology is a quite rapidly evolving discipline because it is both an arts and humanities discipline, and a science discipline, which is great because we can draw on the strengths of so many different experts and disciplines. My wife, Wendy for example, is an expert in micromorphology which is the study of deposits through the microscope, through intact deposits such as sequences of floors whereby we’re able to see the microscopic evidence that people leave behind. Activities like cooking or making tools, or whatever. Also, today there is a major development with ancient DNA, in which increasingly we’re able to recover DNA from humans, from animals, from plants, even from the environment that can tell us so much about things like kinship between people, the relatedness of people. One of the sites we’ve been excavating for the past twelve years or so is a site called Bestansur on the Shahrizor Plain in the Sulaymaniyah province in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. We have there a building dating to about 7700 BC and on the floor of the building are lots of human remains. It has deliberate burial of people under the floor, many of them small children. From some of them, the preservation is not wonderful because the collagen sort of leaches out of the bone, but with some of them we’re able to get ancient DNA and to see how related the people are. And in fact, what that shows so far is a very mixed population, so they have connections up into the high Zagros of Iran to the east, but also to the north, to Syria and towards Turkey, to the north west, so we can tell that the people at that time were very connected. They were moving around a lot and very inter-connected. We can tell that from the A-DNA.

Another technique we use, with our colleague Dr Amy Richardson who works with us, is using portable X-ray fluorescence, which is a technique increasingly applied in archaeology. It’s a non-destructive technique, where you can put an object underneath the analyser and it gives you an elemental reading of the object. That can tell you, in the case of some objects, where they came from. For example, many of the tools at this site from 7700 BC, they’re made of something called obsidian, which is volcanic glass. It’s produced during volcanic eruptions and each volcano has a distinct chemical signature, so we’re able to look at the tools which are found hundreds of kilometres away from their source. We can analyse them and say, yes this comes from this place 500 km away. That’s what we can do with our obsidian tools. We can tell that almost all of them come from a source called Nemrut Dağı, which is near Lake Van in Eastern Türkiye, so a long way from Iraqi Kurdistan. That also shows us that people were very connected and very mobile at that time.

How do the discoveries and research on early Mesopotamian civilisation influence contemporary efforts to preserve and promote cultural heritage in Iraq and the broader Middle East?

There are challenges of course. There’s always the financial challenge. I think Iraq is not unique in that respect. Governments have to allocate funding to protection and enhancement and preservation of their heritage and that ultimately is a governmental choice… what their priorities are. As archaeologists, we lobby and encourage governments and colleagues to invest as much as they can, but Iraq has many challenges to deal with, not only preserving its own heritage. But I think steadily, it is coming more to the fore as a priority. We’ve worked with Iraqi colleagues to do things like develop heritage tourism, which is in its infancy, I think is fair to say. There is a lot of heritage tourism within Iraq by Iraqis, so a lot of Iraqis from south Iraq like to go to north Iraq, especially in the summer when the weather is a bit cooler and more pleasant. They come to see heritage sites, archaeological sites, as well as natural sites because Iraq has lots of natural environmental attractions, as well as the heritage side of things. In some cases, it’s a question of mixing those two together and making a kind of package. There are Iraqi tour companies that we work with who are heavily involved in that. The challenge is then getting outside interest and convincing people that Iraq is a beautiful, safe and lovely place to travel to. That’s going to take time but, you know, step by step.

What lessons can modern societies learn from ancient cultures to protect their heritage?

That’s a very good question. There is so much to learn from the past about ways of behaving, sustainable ways that are in harmony with nature and the environment around. We know that these communities from way back in the prehistoric past did last and even endure for hundreds, even thousands of years, so they were clearly not doing things too badly in terms of impacting their environment. I think local solutions and local situations are the things very much to work on. As the phrase goes; think globally, act locally, so we can’t persuade the whole world to do things but we can engage locally and that’s why we have programmes of engagement with local villages, for example. They work with us on the archaeological sites, they live there when we’re not there, as well as when we are there. Their involvement is absolutely critical in making developments because local communities have to have buy-in to any sort of preservation of sites, protection of sites, enhancements of sites for tourism or any other purposes. It’s absolutely critical and essential that there is local buy-in. There were some studies that have been conducted, in particular in places like Mosul, which of course suffered terribly through occupation and then the expulsion of so-called Islamic state in 2017. A lot of the buildings in Mosul were damaged or completely destroyed and there have been major international campaigns by UNESCO and other international bodies to try and put things back as they were, but what has been lacking has been, to some extent, the local buy-in, consultation with locals. You know, talking with locals and asking: what do you want to do with this ruin of an old church or an old mosque? Do you want it rebuilt as it was or would you want it left as a memorial? Do you want something different altogether? Instead, it’s being more of an outside-in decision of ‘we’re going to rebuilt that, here’s lots of money and let’s get on with it.’ And then the locals are saying: well, hang on. Why don’t you ask us first? And surveys have shown that that kind of engagement is getting better but it hasn’t always been there.

- Published: 6th May, 2024

- Date Taken: 4th May, 2024

- Location: Reading

- Country: United Kingdom

- Editor: Justyna Wojtowicz

- Photographer: Justyna Wojtowicz

- Category: Culture & Heritage